There’s a clear philosophy to successfully fix anything. These are near-universal approaches to just about any technical/interpersonal matter. This idea goes beyond break-fix and repair, and can sit within any domain where a change is necessary.

There are implementation-specific and component-specific details (such as with computers), but that’s not the point of this essay.

The steps may sometimes only take a few seconds, but every fix employs a relatively straightforward, mundane procedure:

- Analyze and identify the purpose that makes the thing “broken”.

- Consider the chain of events that create the thing.

- Observe what exists carefully, and what is precisely happening.

- Investigate the patently obvious things that could be wrong.

- Poke at it to find out more information.

- Reposition perspectives to find even more information.

- Work the edge case if Step 2 failed.

- Investigate complexities to find anything weird.

- Presume harmonizing issues to find really weird patterns that may line up.

- Repeat things to be sure you’re not wasting resources with the fix.

- Get the supplies and visualize the fix.

- Repair and observe what happens.

- Clearly document things that happened and what you did.

It sounds easy enough, but there’s more to it.

It’s all networked

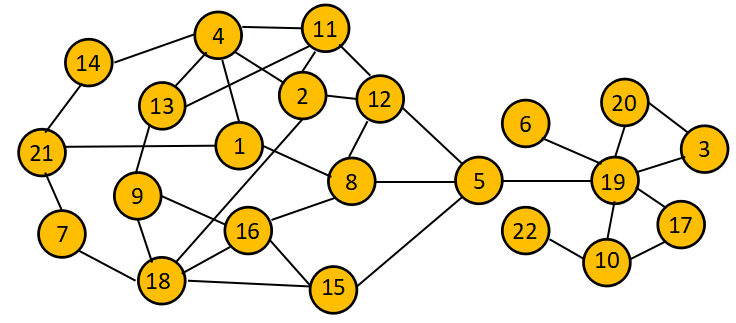

Imagine a diagram of a network with nodes and connections between them:

This network can represent anything that accomplishes a defined purpose:

- A computer network

- A single computer

- An engine

- A building electrical system

- A supply chain

- A social group, large institution, or social network

- A human body, subsystem, organ, tissue of an organ, or cell

- A philosophy, belief, thought, or sensation

Reality is frequently atomic, where every object is the combination of smaller objects. Those smaller objects are the combination of even smaller ones, and so on.

Except for the specific neurodivergent state of autism, most intuitive thinking works in reverse to nature. We imagine the object as a collective unit first, then work downward into details.

Experience allows people to know which of those details affect results and which details are irrelevant:

- A lightbulb will fail before a wire

- Fuses fail before cables

- Alternators fail before starters

- Networks fail before software

In the above example, if node 3 fails, the whole system may go offline, which may make it “broken”. However, the entire thing except node 3 is perfectly fine. It only fails its purpose when someone expects it to do something that passes through node 3.

We can typically salvage the object if we mend or circumvent whatever that broken component is.

Therefore, troubleshooting is knowing where the broken node is.

This isn’t always easy. There are often networks or nodes beyond the current known network. This is a massive reason why great technicians constantly ask, “why?”

1A. Analyze the desired purpose

A network is the “state” of reality, but living beings ignore information dissociated with a predetermined purpose.

“Broken” is a misleading idea. Its best definition is “current events with the object haven’t satisfied the user’s prior experience of cause-and-effect expectations“.

At the beginning, someone doesn’t know what’s wrong. The thing created a result, but now it doesn’t.

Previously known experience is highly useful because it focuses the scope of what could be wrong:

- It specifies exactly what someone was doing when the thing broke, which creates a “start” point.

- The desired result becomes clear, which creates an “end” point.

- Those “start” and “end” ideas together mean all possibilities are “chains” between “start” and “end”. Extra possible avenues branch into separate chains.

1B. Consider the chain

With the above diagram in mind, imagine someone saying, “I tried to make 8 happen, but it’s not doing it”. Without knowing what node they’re observing, it could represent anywhere on that network. The story is entirely different when the statement is, “I tried to make 8 happen through starting 15, but it’s not doing it”.

The first thing, more than anything else, is to find out the chain’s limits.

- If the action going to 8 starts at 16, there are only a few possibilities (16, 8, or the 16-8 junction).

- If there are many possible connections, the cause-and-effect will be harder to simply deduce.

- Each node exponentially adds more possibilities (as a matrix of known issues):

- A = [A] = 1 possibility

- A-B = [A,B,A+B] = 3 possibilities

- A-B-C = [A,B,C,A+B,A+C,B+C,A+B+C] = 7 possibilities

This grid behaves differently whether the nodes are things or people.

- Things give instant feedback or, when there’s a time delay, a predictable response when timed.

- People are complex networks of their own. Every system test or query with people runs the possibility of changing the outcome or network altogether.

Most issues are simple enough for this approach. More elaborate issues require careful perception and changing perspective to see when things work or don’t work.

1C. Observe everything

If you must deduce smaller links in the chain, draw from several approaches:

- Use your intuition and experience to check on what most likely fails.

- Bias easily sways this with experience. There’s no reason to investigate for an obscure cause simply because you read about it in school. This mostly requires hands-on experience, but is the quickest way to diagnose.

- Test something in the middle of the chain.

- If your test can slice the chain of events in half, you’ve exponentially reduced the number of possible problem areas (X/2 => √X).

- To be sure, test both sides of that chain, since it might be two issues!

- Turn off every single feature or option and see what happens. If it doesn’t work, your chain has become much smaller. If it works, sequentially turn features back on until you see something stop working.

Pay close attention to every little detail. The issue could come from anything unusual (e.g., minor scuffs, a strange prompt, an unusual statement).

When a breakdown creates severe risks, it’s not uncommon for our bias to blind us to the patently obvious.

- We tend to imagine adverse consequences of a sustained failure, and it’s wisest to kill those thoughts.

- We often ignore the dumb and obvious reason because we imagine the phenomenally unlikely experience we heard about once.

The answer to a far-reaching problem is frequently a mundane and common fix.

- For that reason, it’s typically worth asking the intuition of the least-educated or qualified person in the room.

2A. Investigate the obvious

Many times, the end user or consumer will have a hard time understanding the specifics of their problem. In their lack of understanding, they’ll lose patience with the fact the problem persists.

- The user/member/patient often says something vague:

- “My car won’t turn left.”

- “The computer won’t turn on.”

- “He is a bad person.”

- If you can, ask for key information about precise elements as the event transpires.

- Avoid jargon or diagnostic terms, since they might start misstating that jargon to feel important (e.g., “Yes, my brake caliper was making that noise.”).

- This serves several functions:

- To the degree of their perceptiveness, you won’t have to revisit everything they’ve experienced in-person.

- They may become aware that there are more details than they were originally aware of, which may give them more patience.

- They become informally trained on what to perceive in the future, which can profoundly impact an entire group’s corporate culture over time.

Keep an eye out for the XY problem, which scales dramatically as systems become more complex:

- The user’s inexperience leads them to the details of X when they’re trying to solve Y. X and Y are entirely unrelated.

- Repeated support tickets and requests open up for the user’s X problem.

- Those tickets promptly close as highly qualified people consistently fix X.

- The user becomes increasingly frustrated until one of several conditions happen:

- They either give up (and solve their problem without that particular product).

- Someone in the organization notices that everyone keeps fixing X.

- Someone else notices Y in an unrelated situation and leaves the user confused but satisfied.

2B. Poke at it

While completely focused, test it a few more times (if possible) by changing the origin and destination locations:

- Remove the farthest-outputting part and watch what happens.

- Feed in a different input, such as hand-cranking, or vary up the quantities.

- Insert a new input or output that gives more or different information.

- Plug in another known-good screen or try a different mouse.

- Access a different website or talk to a different person in that group.

- Use a different computer on the network or try a different operating system.

- Try a different fluid, or remove the extraction pump.

- Use a different thought experiment.

2C. Reposition perspectives

To get more information, it helps tremendously to shift around perspectives.

- Look at it from multiple angles. We only sharpen this skill through creative thinking, which we can train.

Smart people tend to be better at finding problems.

- One definition of intelligence is “a person’s ability to maintain multiple perspectives at once”.

- This capacity magnifies if they have a favorable neurodivergence like ADD, autism, or schizophrenia.

- However, smart people are also slower to act. Sometimes, just throwing things at a problem gives enough information.

The range of perspectives compounds proportionally to the complexity and bad design decisions of a system.

Ironically, while redundant systems can be very useful to prevent failures, they make it more difficult to diagnose them.

- Assume A leads to B. Assume there are two more backup systems to lead A to B. This makes three systems to verify instead of one.

- To discover the problem, create explicit distinctions between each system (i.e., severing connections, alternate inputs).

- This mindset is mostly why hackers are the best technicians.

By this point, you’ll have figured out 95% of the issues you’ll ever encounter.

3A. Work the edge case

By this point, you’ll typically see the issue and know what needs replacing. However, there’s a comparatively smaller chance the cause of the issue won’t arise in a blaze of clarity.

The next step is to whittle away things it can’t be. Your purpose should be to make the likely chain of issues as small as reasonably possible:

- If it doesn’t create any adverse consequences, try to reproduce the issue again, but with different inputs.

- If it does create adverse consequences, ask for volunteers to experiment (which may be the end-user in some scenarios).

- Examine other ways to break the system the same way.

Generally, understanding likely things that fail is the best preventative measure. It requires gleaned experience, though (either yours or others working with the items in question).

- This is recursive unlikelihood: something broken is already unlikely, and the likely fix isn’t working, making an unlikely unlikelihood.

- Constant changes in an industry can quickly deteriorate any gains in this domain.

3B. Investigate complexities

Finding a cause becomes more difficult proportionally to how much complexity is in the system. Elaborately designed things (e.g., computers) almost guarantee you can never be 100% sure about any solution.

- Error-tracking systems cut down heavily on the need to investigate. It’s another system, though, which could also fail (e.g., engine codes are electrical signals).

For this reason, most advanced troubleshooting uses more in-the-weeds technical controls to keep the chains as small as possible:

- Command-line prompts remove the uncertainty of a bad GUI and allow the user’s input to be more precise.

- Before computerized throttle controls, auto mechanics operated the throttle on top of the engine instead of the accelerator.

- Philosophers tend to imagine idealized scenarios instead of practical considerations that complicate matters.

- Expert conflict managers tend to use low-context and simpler language.

3C. Presume harmonizing issues

Some edge-case issues can cause technicians to lose sleep trying to figure out why:

- Two relatively innocuous edge cases can create unique and difficult-to-reproduce. One trivial failure will frequently interact with another trivial failure, making an entire system fall apart with zero intuitive predictability.

- Occasionally, a connection between two elements can be defective while the elements themselves are known-good.

- Another hidden risk in diagnosing problems is when the chain has two or more points of failure.

- Rolling out an update can break things. When something updates, it’s no longer known-good. Always keep backup versions ready to roll things back until you’ve implemented every applicable case.

Synergistic issues come more frequently in the presence of human failings:

- Inherent design or engineering flaws

- Poor maintenance

- Previous people who “fixed” it incorrectly

If you don’t know, expect neglect and for more issues to happen soon.

4. Repeat things

Since you’d prefer to not revisit the issue, you need to be 100% sure you’ve replaced all non-working components.

This part here is the most tedious portion of diagnosis, but is also often the most overlooked.

- People with personalities good at finding problems also typically don’t like checking their work.

- People often skip this one, especially if they’re impulsive or not particularly intelligent.

In human interactions, duplicating the scenario is typically impossible (since people respond differently each time). It requires a combination of finely-tuned intuition and imagination.

It always requires at least 2-3 perspectives of that one part to get an accurate picture. You won’t know until you’ve tried it a few ways.

Every single part has at least two aspects to it:

- The part’s inner workings that do things (e.g., the database, the compressor’s parts).

- That part’s connection to other things (e.g., the GUI for the database, the plumbing to the rest of the unit).

It’s typically difficult to tell at first glance with any degree of authority what’s actually wrong. When there were bad design decisions, this gets much worse.

- The car not getting power may be from a bad battery, a bad alternator, or a blown fuse box.

- The forgotten message may be from a bad messenger, poor interpretation, or a vague message.

- A failed command may be from a bad API, a bad command to the API, or a bad network configuration.

- Failed recipes could be bad instructions, bad ingredients, or bad cooking skills.

5A. Get the supplies

To fix things, you need parts or supplies. When you have what you need, swap it out and close the ticket.

- Since your time is important, you can add the old part into a “fix later” pile. It gets things back to running immediately and you can close the ticket.

- This, however, requires that you actually order the replacement parts before they’ve failed.

The easiest solution, if it’s attainable, is to get an identical copy of the thing:

- For software, this is trivial on an internet-connected computer (or an OS with a reliable backup schedule). It may simply require copying drivers from another computer.

- For hardware, you will have to have a good inventory management policy beforehand to have parts ready to go.

- Arrange for logistics for new components beforehand. This is a significant aspect of good management.

- However, it can become horrifyingly complex if the components are extremely rare or an organization’s security policy becomes Orwellian.

5B. Visualize the fix

It doesn’t have to be complete, but that person must be able to imagine where all the resources are located.

There are 3 distinct phases in any repair job:

- Disassembly – remove everything that may obstruct convenient access to the problem.

- Keep everything neatly arranged and labeled to allow the final phase to operate smoothly.

- For social contexts, this represents as finding a quiet and safe time to talk with someone.

- Repair – directly access the problem area to swap out a component.

- Any new issues are a recursion of this 3-phase system, but smaller.

- If the component is a cable, securely attach the end of the new cable to the end of the old cable, then yank the old cable out and detach its end, leaving the new cable.

- In social issues, this is extremely difficult because the individual may not want the fix. At that point, consult ideal conflict-management approaches.

- Assembly – combine everything back together.

- For a physical object, securely tighten everything in place to prevent it from moving later.

- In social contexts, this means carrying on as if nothing had happened.

6. Repair and observe

This requires watching exactly what happens to be sure it works correctly, which is frequently easier with a second observer.

- Having a witness to the fix also keeps the technician legally safe from the accusation they didn’t fix it.

It’s always a good idea to keep tools available and in working order. While your needs will vary by industry, it’s almost always worth keeping a few tools around:

- A high-quality multi-tool

- Hammer

- Variously sized screwdrivers

- Needle nose and snub nose pliers

- Crescent wrench

- Hex wrench set

- Utility knife

- Protective gloves

- Headlamp and flashlight

Both the decay of any individual part and discoveries of failures usually work on a logarithmic curve. Unfortunately, in gargantuan systems, lots of time can transpire between events. With enough time, everyone forgets what happened last time or all the familiarized technicians no longer work there.

When updating, make sure the thing is as immovable as possible. Particularly savvy people update/replace on-the-fly, and sometimes multitasking:

- Always secure and ground the objects you’re working with, even if it’s with tape.

- Keep everything organized to prevent something interacting inappropriately.

- Never permit distractions to an important conversation.

- Keep everything labeled as you go.

- During critical stages, never make more changes than necessary.

Many managers imagine breakdowns are a great time to upgrade. This is only a good idea if it’s replacing an entire system. That upgrade will likely make more things fail later at the juncture between the new thing and the old one. It’s only cost-effective if it worked elsewhere.

7. Clearly document things

It’s dead critical to thoroughly and precisely document what you actually did:

- If something failed, it may fail again and represent a different issue along the chain.

- Clarify any slight deviation from what it was before you touched it.

- Even if it’s your solo project, memory is fickle, even 2 days later.

If you don’t write it down, it didn’t happen.

A note on technical debt

“Technical debt” is creating future work by badly fixing something right now.

- A “duck tape and baling wire” solution is always available.

- It “fixes” the problem, but isn’t durable enough to withstand heavy use.

- That “fix” will mean a failure in the near future.

- An actual fix will be more expensive later to undo the earlier “fix” to make the work environment workable.

Technical debt is only worth the cost in two circumstances:

- You have an emergency.

- You’ll soon be decommissioning the system.

Frequent emergencies come from lots of technical debt. At that point, consider investing into a better system.

Technical debt isn’t a big deal with an edge case, but will destroy any efficiency gains on a common case.

Technical debt lingers with the object. This can be dramatically severe in a long-term project.

Documentation can help curb at least some technical debt, but the best cure is to never have it. Most people want to ship quickly, so this is against human nature.

From the beginning, think months and years ahead. An edge case can become the de facto common case after a long time, especially after frequently using something. Things frequently scale over time, so it’s often not a question of if, but more of what.

One particular example is any fix that involves tape. Connecting two parts either needs a more robust securement (e.g., adhesive) or a better solution (e.g., plumbing or welding).

A note on long-term improvement

As much as possible, keep spare resources around before you need them.

- This applies to spare parts, especially the most likely parts which could break.

- You’ll frequently need more time than you’d expect to diagnose problems.

- You’ll also need plenty of space to work in.

- As you scale, assign a designated area (e.g., a workbench) with all the necessary parts and space. It’s sometimes worth hiring someone to help with fixing as well.

Frequently, a network has a distinctive pain point where stuff breaks down more often. There are several ways to work through it:

- Keep swapping out the components, which can be time-intensive and won’t scale well.

- Find a way around it, which may require clever hacks. Sometimes, if it’s better than the original solution, it might become the new standard.

- Invent something that creates the desired result from an entirely different angle.

Some perfectionists obsess about getting everything “just so”, where the object is as immaculate as possible. However, the tradeoff for this is typically not worth the effort, and they should settle for “good enough”.

For this reason, the most skilled people at repairing also often become inventors and start businesses.