TL;DR

Successfully changing has multiple components, so setting goals gives us the means to accomplish them.

Start with what you want to see happen.

Don’t worry too much about long-term goals, since they won’t be that useful.

Instead, focus on the short-term reality laid out in front of you.

Merge all your goals into one system, simplify them, then divide them out into small tasks.

Plan out your days and weeks as they happen.

You can mix-and-match many existing systems to make your own.

Learn to boldly say “no” to things that interfere with your goals.

Focus more closely on well-managed time and energy than achieving results.

To actually accomplish anything, do not discuss your goals.

Periodically re-examine your goals to make sure they’re still worth your time.

Why make goals?

Successful change has multiple necessary components:

By not setting goals, other people and circumstances will set them for you.

- Appropriate goals only come through experience setting bad ones.

Stay both realistic and ambitious.

- Many people imagine bad goals come from poor time management, but they’re usually from poor stress management.

- You must have currently unmet expectations you know you can achieve.

Start with the results you want

Begin by asking questions:

- What occupies most of your time?

- What do you want to achieve?

- What are my obstacles to it?

- Who else has done this already?

Visualize the tasks you want to achieve:

- Visualizing isn’t useful for framing your future status, but is critical for understanding specific parts of the goals you want to achieve.

- Finding motivation requires that we fully understand our purpose.

- Visualizing creates a sensory connection of experiencing, seeing, and feeling through intense imagination.

- Every successful person visualizes their purpose before they’ve created any results.

Whenever possible, try to avoid competing against the masses:

- If you’re competing against many people, sheer probabilistic chance gives you a disadvantage.

- Instead, aim for things that have a much smaller set of people competing for that space.

- Preferably, if you’re the only one doing something, then you’re safe from people trying to imitate you until they catch up.

Ask who you want to be in 5 years and list at least 10 attributes of each part:

- Your future outlook on life

- The routine of your future typical day

- Your future job

- The things you’ll be looking forward to

- Your future family

- The people in your social circle and your closest friends

- Your future physical appearance and fitness

- Your future home

- How you will manage conflicts and hardships

- What you want people to remember you for

Ask dumb questions to find obvious problems:

- Why do I do (action), and what makes me do it?

- What do I dream about or love doing, and what has kept it from happening?

- Which skills am I good at, and how can I use them more?

- What do other people need, and where do they need it?

- Which opportunities can I use to expand my worldview or learn what I want to learn?

- What strengths and weaknesses do I have right now?

- What opportunities and threats surround me?

Practice brutal honesty with yourself to find in-depth problems:

- State out loud, “Everything in my life is fine,” then pay close attention to any objections you feel

- If your life is going horribly, anything different than what you currently have been doing is a good start.

- Write down your top 5 problems in your life, then ask why you haven’t done anything about them

- Long-held beliefs, prejudices, and assumptions

- Communications with others

- Mindless routines and habits

- Insufficient time, energy, or resources for your goals

- “Voids” of wasted time, energy, or resources

- Your worst fears

Categorize your goals in relation to how far away they are:

- You should have assembled enough goals that you can place at least a few into each category.

- Short-term goals are things you can technically accomplish right now.

- Mid-term goals look out beyond a year, but before 5 years.

- Long-term goals span 5-15 years.

- As you make the goals, you should be able to feel that your tasks will naturally reflect all three domains at once.

Use the R2/A2 formula to draw personal goals from other people and characters:

- Recognize their principle, technique, or idea.

- Relate their principle, technique, or idea to your experience.

- Assimilate the principle, technique, or idea as part of yourself.

- Action it by doing something to prove you now live by it.

When you’re done, distill the goals:

- Write a “personal leadership code” of 5–10 principles or purposes you wish to live by.

- Place those rules somewhere prominently.

- Every year, review those rules to be sure they still apply.

Long-term goals are only somewhat useful

It feels nicer to be partly finished with a longer journey than starting a shorter one, but most large goals take at least 5 years to accomplish:

- It often takes longer than you think because you’re completely incapable of realizing all the challenges along the way.

- It’s also impossible to stay motivated when things don’t work out the way you expected.

Long-term planning only helps our pacing and focus:

- The most dramatic side effect of long-term planning isn’t from the actual plans, but from how we meditate heavily on the goal.

- Without long-term plans, we often don’t know when to stop or reconsider our actions.

- If we don’t expect to follow through with a goal, it’s better to save the discouragement and not start at all.

Expect to fail most of your large goals:

- If you aim for 20 BHAGs (Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals), you’ll probably only do about 3 of them.

Instead of focusing on goals, work on making better systems:

- Good systems allow you to build toward ideas and should be flexible to adapt to changes in life.

- Goals, on the other hand, can be discouraging if they’re not correctly set.

- A good system is simple enough to easily provoke you to act, but sophisticated enough to capture your ideas.

Start small

Don’t focus on becoming extraordinary:

- Extraordinary people did above-average things every day for a long time, which required them to simply push themselves slightly more than they were comfortable each day.

- Making small improvements you can stick to over a long time always yields more results than a large-scale ambition.

- While each person can become extraordinary, they started with unremarkable sacrifices.

- To believe you can achieve something, you must start with something small.

- We experience a psychological reward when finishing a task, so start something you can finish quickly.

- Aiming for smaller goals has the advantage of building momentum toward larger goals later.

- Even skills for managing a large organization or starting a business start with remembering to floss every day or do laundry.

Create a clear statement or two about what you want:

- By clarifying what you want, you free up your mind to focus on getting there.

- Jargon and technical terminology separate you from the statement’s meaning, so avoid them as much as possible.

- Avoid extremes and always/never statements, since they tend to foster mental illness.

- Set clear deadlines with a follow-up date to examine your results.

Work within the reality set before you and what you’d like to see differently:

- Work forward from your opportunities, not back from some long-term vision.

- Contrary to most success “advice”, your goal will change much faster than your natural abilities and situation.

- If you must think long-term, imagine the future position that will give you the most opportunities, not the ones that make you happiest or seem most promising.

- Clearly define what your problems are.

- Figure out all the things that would most likely guarantee failure.

- Carefully consider actions you can take to avoid every one of those things.

Merge all your goals into one system

You’ll need multiple media and software because you’re trying to capture all your ambitions and thoughts:

- Paper, notebooks, sticky notes

- To-do list and note-taking software

- Journals

- Gantt charts, mind maps, spreadsheets

Your system will be highly personalized:

- Create a natural flow from your brainstorming into results.

- Use any medium you feel adds value, and avoid what you don’t like.

- Constantly look for more ways to slice and capture your information better.

- If you want a system that lasts more than a few years and is on a computer, make sure you can directly access the files with at least two or three free software programs (e.g., text files, .doc files).

After capturing all your ideas, simplify them

You’re not going to easily organize things as they come in:

- You can only organize after you know what you want to do.

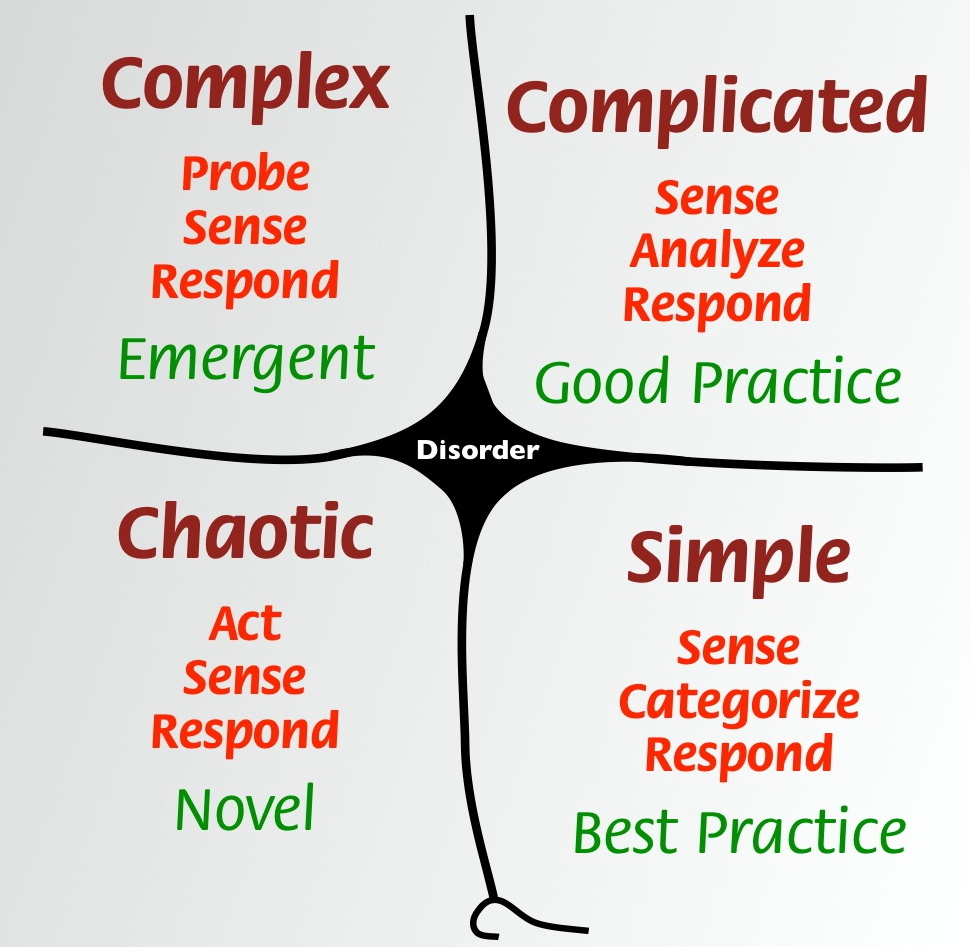

Problems are either simple, complicated, or complex:

- Simple problems are relatively straightforward, even if they have many steps (e.g., most cooking).

- Complicated problems can also be broken down into steps, but there’s no straightforward system to easily use for them (e.g., building a rocket).

- Complex problems are elaborate, interdependent situations that are difficult to simplify (e.g., parenting).

Many goals are smaller pieces of larger ones:

- Remove unnecessary steps or spin them off into projects.

- Group ideas to understand your ambitions.

Assemble everything into a plan and then attack it:

- After you’ve made your plan, imagine you’ve received a vision that the plan is doomed to fail, then ask why it would.

- Expect every possible thing that could go wrong, then make plans for those.

By the end of your planning, you shouldn’t be surprised by almost anything that may fail.

Divide your large goals into smaller ones

Make your smaller, or “actionable”, goals as practical and simple as possible:

- If the task breaks into multiple days or multiple parts, it needs subdivision.

- Vague tasks need more clarification, which may require spelling out exactly what to do.

- Every task will start with an “action” verb:

- Single-step verbs only take a few minutes:

- Book, brainstorm, buy, call, copy, discuss, draft, edit, email, fill out, find, gather, load, outline, print, purge, read, record, register, research, review, schedule, verify, wait for, write

- Multi-step verbs take hours or days:

- Analyze, build, complete, decide, design, ensure, finalize, finish, handle, implement, install, launch, look into, maximize, organize, research, resolve, roll out, set up

- Single-step verbs only take a few minutes:

Every large goal must have at least one task you can finish right now, today.

If you’re stuck, ask what you need:

- What do I need to create results?

- What skills do I need?

- To make it happen, what resources am I missing?

- What can I control to manage things currently beyond my control?

Estimate how much time each task will take.

Divide any task that feels too large to perform right now into smaller tasks.

Even if you keep postponing it, give a deadline for every task:

- We tend to postpone tasks without deadlines forever.

- Without a specific end date, we tend to become perfectionists or lazy.

Group your tasks by where you’ll perform them or what you’ll need:

- Use tags, titles, highlights, and categories liberally.

Plan your days and weeks

Schedule time to plan the week or day before it starts.

Honor the Three Back-Job Rule: three jobs hide behind most tasks you can see:

- For this reason, large-scale success can take up to four times as much work as you’d expect.

- After you’ve made goals you know you must do, don’t think about anything but the present task.

Use the 2-Minute Rule: do anything immediately if it takes 2 minutes or less:

- If you don’t have time, make a “2 Minute List”.

Only plan tasks you can visualize doing:

- You should be able to finish the task in the specified time.

- Add room for comfort and error between tasks.

Only plan up to 8 tasks each day:

- To avoid wasting time, prioritize the most important tasks at the top.

- We can only complete 6–8 tasks on any given day.

- List fewer tasks you know you’ll finish instead of many you may not get to.

- If you’re done and have time, you can always do something else as a bonus task.

Cross off or delete completed tasks as you finish them:

- Aim for To-Do List Zero every day, where there is nothing left on your list.

- Either reconsider the value of everything you couldn’t finish, or move it to the next period’s list.

Don’t get too consumed by technology:

- While there are many ways to manage your to-do list, the best solution is often the simplest.

- Start with a plain text file or notepad, then work your way up as you need degrees of complexity.

- Technology gives many answers to problems, but the wide variety of options can be very time-consuming.

- Regardless of what system it is, it’ll eventually fail at something.

Take inspiration from existing systems

Your system should be subordinate to getting things actually done:

- You can use any combination of existing systems to build your ideal goal-setting system.

- The system must simplify how you actually do things, and shouldn’t be any more complex than you need.

- This is a creative process, so the entire system will move around as your mind adapts to productivity.

The Action Method

- Action Items — steps to get the project done.

- Back-burner Items — interesting ideas that don’t quite fit into the project.

- Reference Items — resources and information for completing the project.

For cleaning up creative brainstorming.

Agile results

- Set three outcomes you want for the upcoming year.

- Set three outcomes you want for the upcoming month that line up with that year’s goals.

- Set three outcomes you want for the upcoming week that line up with that month’s goals.

- Set three outcomes you want for the upcoming day that line up with that week’s goals.

- Perform the day’s or week’s tasks.

- Adjust at the end of the respective periods for the next periods

For goal-oriented people who want a complex timeline.

Biological Prime Time

- Remove any factors that may mess with your energy, such as caffeine.

- Record what you’re accomplishing each hour you’re awake.

- Search for patterns in your biological rhythms after collecting productivity data.

For people who like measuring everything.

Bullet Journal

- Make a categorized index at the beginning of the document, which you’ll add to as you add components.

- Write out a future month-by-month log of general tasks you need to do.

- Write out a daily log to indicate daily activities.

- Use “signifiers” as bullet points to indicate specific needs you have (task, note, event, task migrated, task scheduled, task complete, etc.).

- Organize your monthly goals into categories.

- Store collections at the back of the document you want to accomplish across a year.

- Cross off items as you complete them, and transfer important uncompleted tasks to the next month.

- More info here

For people who are constantly disorganized and find productivity systems difficult.

Cynefin Framework

- Simple things are inherently obvious, so they need sensing, then grouping, then responding to them.

- Complicated things are “known unknowns”, so they require sensing, then analyzing them, then responding.

- Complex things are difficult to understand, so they need probing further, then sensing, then responding to them.

- Chaotic things are completely unknown, so they require acting on them to find out what they are, sensing what they are, then responding.

For people who are incredibly uncertain about numerous things.

Organize the problems by their constraints and associations with other things.

Decision Matrix

- Write down all the options on the left side of a piece of paper.

- Write each of the factors you want to consider across the top.

- Give each of the options a “score” based on each factor.

- Total up the scores to figure out the best decision, and give weight to factors if you want a specific decision.

For people who can’t make up their minds.

Don’t Break the Chain

For people who have a difficult time honoring convictions.

- Declare a small and intentional routine or habit you want to stop or start.

- Every day you do the task, cross off the day on a paper wall calendar.

- Try to avoid “breaking” your chain of days.

Eating Live Frogs

- Order your tasks from hardest to easiest:

- Things you’d rather not do, but must do

- Things you want to do and must do

- Things you want to do but don’t need to

- Things you’d rather not do and don’t need to

- Work on the hardest task first:

- The most important

- The most uncomfortable

- The most mind-numbing

- The most difficult thing to do

For procrastinators who miss deadlines or rush their work.

Inspired by Mark Twain’s quote, “If you eat a live frog in the morning, nothing worse can happen the rest of the day.”

Eisenhower Method Matrix

- Urgent things are seldom important, and important things are rarely urgent.

- Most people move to Quadrant 3 from Quadrant 1 because Quadrant 2 never feels necessary.

- Productive people move to Quadrant 2 by disregarding instant gratification.

For people who feel controlled by urgent things.

Only do what is important (i.e., “above the line”) and disregard urgency.

Emergent Task Timer

- Make a vertical list that categorizes everything you do all day, with a few additional entries for miscellaneous needs.

- Make a horizontal list indicating every 15 minutes of that day.

- Set a timer for every 15 minutes.

- Record what you do every 15 minutes, backfilling if you can’t get to it.

- Review what you did after you’ve accumulated data, noting patterns across days and weeks.

For people who don’t trust their ability to focus.

Getting Things Done (GTD)

- Collect every single thought, scrap, process, and idea into one “box”.

- Run everything through the GTD Flowchart:

- Organize the results backward from large-scale goals:

- Define your greatest purposes and principles.

- Visualize the outcome you want that fulfills those purposes and principles.

- Brainstorm how to create that outcome.

- Organize what to do to achieve that outcome.

- Identify the next actions to achieve your purposes and principles.

- Routinely review what to do next:

- Make a “Tickler File” of 43 folders (31 for each day and 12 for each month).

- Review the Tickler file each day and month to remember what to do.

- Purge tasks and clear out old or obsolete things.

- Do your tasks based on available time and energy, context, and priority.

- More info here

For people who want to organize plenty of loose ends.

Interstitial Journaling

- Every time you take a break, record the time and a status update.

- Record each time what you want to do, and how well you’ve done it.

- Review the entire day after you’re done.

For people who have a difficult time focusing.

Must, Should, Want

- MUST — non-negotiable.

- SHOULD — also important, but not for today.

- COULD — whatever you want to do that isn’t necessary.

- WOULD — may make sense if it didn’t drain so many resources.

For people who want prioritized lists more than graphs.

Group tasks into categories of MUST, SHOULD, COULD, and WOULD.

The Paper Clip Strategy

- Specify a task you want done more than a few times per day, then put that many paper clips in a container.

- Place one paper clip in a second container when you complete the task.

- Empty the paper clips from the first container by the end of the day.

For staying focused when you want to automate your work.

The PARA Method

- Projects — short-term efforts in your work or life that you’re working on right now.

- Area — long-term responsibilities you want to manage over time.

- Resource — topics or interests that may be useful in the future.

- Archive — inactive items from the other three categories.

For staying focused when you have many projects and many responsibilities.

Classify all the information in your life into four major domains:

Personal Kanban

- Set up “boards” as columns from left to right. (Trello is an online solution)

- Label the boards at the top.

- Not Started

- In Process

- Completed

- Place all the tasks on the boards.

- Break out even more boards to capture all the phases of completion.

- Move all the tasks across the boards as they’re completed.

- Subdivide and separate partially completed tasks.

- If you need to, arrange the board into a grid by placing Priority or Members as a vertical dimension for the tasks.

For people who dislike planning and seem to have plenty of unfinished projects.

The Pomodoro Method

- Break down all tasks into pieces that take less than 25 minutes.

- Focus on that task alone for 25 minutes, then take a 5-minute break (aka a Pomodoro).

- Do 4 Pomodoros, then take a 30-minute break or end your day.

For getting things done with plenty of distractions.

Sivers’ People List

For people who want to keep in touch with many people without relying on memory.

- A list — valuable people, contact every 3 weeks

- B list — important people, contact every 2 months

- C list — most people, contact every 6 months

- D list — demoted people, contact once a year to make sure you still have their correct info

The SMART System

- Specific — numerous details (SCHEMES acronym)

- Space — is there room for it?

- Cash — can you afford it?

- Helpers/people — are the right people able to assist?

- Equipment — do you have the right tools?

- Materials — do you have enough to finish?

- Expertise — have you researched to the point of thorough-enough understanding?

- Systems — do you have something to do it with?

- Measurable — how much or how long?

- Attainable/Assignable — who can do it and when?

- Realistic — given everything, is it possible?

- Time-based — what’s the deadline to re-evaluate progress?

For people who have a difficult time making their goals connect to tasks.

Systemist

- Take your system everywere.

- Capture everything you have, the moment you think of it.

- Break the tasks into small pieces you can reasonably do quickly.

- Prioritize the tasks with due dates for anything that’s important but not urgent.

- Every day, get to to-do list zero.

- Measure your progress over time and keep adjusting your plans.

For people who want to organize plenty of loose ends, but don’t want to take the time to organize their tasks.

The Theme System

- Set yearly “themes” for what you want to do, with ideal outcomes for each.

- Write out daily journal entries on how you’ve done in light of those large-scale themes.

- Track daily measurable habits to see how well you’ve persevered.

For people who have vague feelings about what they want to do, but can’t connect them to their daily activities.

Timeboxing/Time blocking

- Group tasks by the type of work they’re made of.

- Estimate how much time each task will take.

- Block off specific times of the day for specific types of work.

- Enforce each block with a timer.

For fighting against interruptions and distractions.

One popular variation is Day-Theming, with each weekday dedicated to a type of work.

The To-Done List & To-Don’t List

- Start with a To-Done List

- Record what you finish.

- Focus on your progress alone and ignore incomplete tasks.

- Review the To-Done List at the end of each day.

- When tasks stay incomplete, make a To-Don’t List

- Write down a list of activities, bad habits, and distractions that get in the way of your productivity.

- Check off each To-Don’t as you avoid each of them.

For people who have concerns about unfinished tasks.

And, if all the above are too complex, just use a single text file.

Boldly say “no”

You have a right to firmly and graciously say “no”.

In fact, saying “no” is the only way to create time in your schedule.

Saying “no” is always harder than it sounds:

- The word “no” is a boundary you or someone else could dislike.

- People with low emotional intelligence are usually offended by the word “no”.

Declining tasks is easy if you know your priorities:

- Saying “no” to something is saying “yes” to something else.

- Rebuild your goals for new purposes, but never do anything outside them.

The alternatives to saying “no” are worse:

- Evading people creates false expectations.

- Saying “yes” ensures you never have enough time.

- Compromising is often a variation of saying “yes”.

You have many polite ways to say “no”:

- I have too much on my plate right now./I can’t fit anything else into my schedule.

- I don’t know when I can do it, but I know someone who can help you right now.

- I can help you tomorrow, but here are some resources that can help you today.

- Please ask me in a week/month/year.

- I would, but only if you’re okay with me dropping [task] to do it.

- Can we talk about this later?/Can you please ask me later?

- I wish I could help, but I’m trying to cut back.

- I want to help, but I would like to focus on your task without distractions.

Say “yes” to what you want by saying “no” more:

- Review anything you’re instinctively saying “yes” to:

- Consider the worst thing that could happen if you don’t do a task.

- Systematically purge anything irrelevant.

- Renegotiate commitments as soon as you realize they’ve become burdensome.

- Move ego-boosting activities that aren’t helping you or others:

- Attending a club that doesn’t challenge you

- Church activities that don’t grow or help anyone

- Sitting on a volunteer board

- Pontificating about successes with others

- Unproductive tasks you’ve mastered

Manage daily time and resources

We tend to adapt our work to meet expected deadlines:

- Assigning 2 hours may turn a 30-minute task into an hour.

- Assigning 20 minutes can make a 30-minute task low-quality or stressful.

- Without experience, our subconscious tends to estimate ideal circumstances, so always add 20% more to it.

Great time managers live in the middle between lackadaisical and frenzied:

- Sharpen your understanding of time by testing specific lengths and deadlines for tasks.

- Give extra room in your schedule to think, plan, and fail.

- Most people use some tricks to “feel” through their events:

- Declare what they want

- Keep a productivity journal

- Make a story about what happened

Energy is usually easier to manage than time because we can feel it.

We should measure time and energy because measuring results can be discouraging:

- Results are volatile and can usually be delayed.

- Most successful people track how well they change their habits.

- Some people try to manage work, but our time estimations are usually very inaccurate.

“Work/life balance” is the art of separating personal time from work:

- It might feel counter-intuitive, but planning for leisure time gives room to relax and recuperate.

- In fact, the world’s greatest ideas usually come from people relaxing or doing something unrelated.

Don’t talk about your goals

Talking about our goals gives us the same chemical satisfaction as accomplishing them:

- Since talking is easier than doing anything, talking about them removes the motivation to perform.

We can circumvent that release by expressing excitement in the future tense:

- “I can’t wait to finish my book!” instead of “I’m writing a book right now.”

- “I’m eager to show my new design.” instead of “I’m making a design.”

- “I want to share my findings.” instead of “I’ve been researching that subject.”

Periodically re-examine your goals

Adapt and update your goals to keep yourself accountable:

- Revisit them monthly, weekly, or daily, complexity-depending.

After you’ve gained some experience, consider the difference between your strategy and tactics:

- Strategy influences long-term effects, so you should consider it carefully.

- Tactics, on the other hand, create short-term results that become immediately apparent.

Always revisit goals and question methods when you fail:

- Make your unfinished goals smaller.

- Consider new pathways with your current position.

Reconsider your purposes:

- On the way, our original passion can completely shift.

- We should always ask if our “finish line” is the same.

- Align any new short-term goals to existing long-term ones, and vice versa.

Ask what you’re doing:

- What you can do to improve

- What you’re doing that you shouldn’t

- What you’re not doing that you should

- Whether other people are benefiting from your actions

- The degree of investment you feel toward your goals and tasks

Ask how others see you:

- The things you should or ought to be doing

- What do other people think about your goals

- Whether you’re marketing yourself enough

- Whether your network is growing well enough

- How much you’re honoring what you promised

Make a personal performance review:

- How much skill you have or developed

- How much knowledge you’ve learned

- Your ability to handle the burden of your workload

- How much you’ve changed

- The quality and quantity of your communications

- How fast you respond to others

- Your ability to focus by yourself

- Your quality of work in a group and delegate responsibility

- How you make others feel and respond

- Willingness to take on more responsibilities

- How consistent and reliable you’ve been

Ask what you have left:

- How much you’ve done

- The remaining number or scope of tasks you have left

Reflect on any consistent thought patterns:

- Natural assumptions you’re making

- Habits you’re slowly developing or losing

- The things you spend the most time thinking about and doing

Be realistic:

- You won’t get to do everything you want to do.

- Your estimations about your capabilities and others’ are usually way off.

- Whenever possible, avoid bias by measuring with numbers instead of comparisons, or compare yourself to your past self.

Start performing when you know what to do

You will succeed through many, many small tasks and habits, but only if you actually start.

If goal-setting is causing you trouble, you’re doing it wrong:

- The entire reason you’re setting goals is to create certainty about what you want to do.

- The goals can’t be so specific that you lose the overall reason you’re doing the goals in the first place.

- If you have too many goals you’ll focus on the easy ones to simply cut down the pile.

- If the goals are too short-term, you won’t see desirable results beyond a few years’ time.

- If your goals make you more anxious than excited, you are not pursuing your passion.

Once you know what to do, your best results come from starting into the task, then optimizing your routine.

This page is Part 3 of my How To Succeed Series. Part 1 was Defining Success. Part 2 was Attitude Adjustment.